Priming and Prejudice

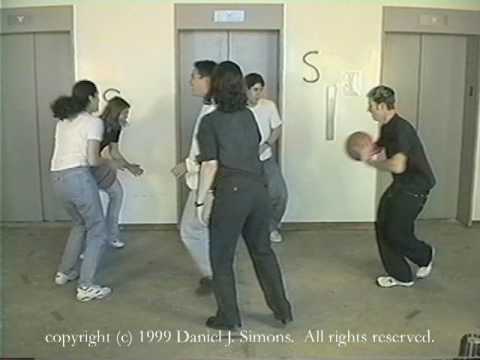

If you have never done so, watch this video, then meet me down below and we'll talk.

Pretty cool, right. So aside from being a neat little feature of how our minds work what does this have to do with families and couples? This experiment is a great way of demonstrating "priming". We are focused on what we are primed to experience and miss what we aren't primed to see. In the case above we are primed to see basketballs not gorillas. Having our limited attention focused on the basketball means that we have less attention for noticing the bizarre detail of the gorilla.

This has very real implications for human interactions. Confirmation bias is a kind of priming in which we give great weight to cases that confirm an idea we have about the world and discount cases that don't confirm our idea. If I believe that tall people are untrustworthy, I will see examples of tall people behaving in untrustworthy ways and view them as representative, but I will tend to discount examples of tall people behaving altruistically. This explains why more pernicious prejudices like race prejudices become re-enforced and are so hard to break. Here's a great example of racial priming.

These aren't bad people, but both black and white people are primed to see a young, white guy as a parks employee and a young, black guy as a thief. If you want to check out your own priming on race and a variety of other social factors, check out ProjectImplicit and try one of their tests that allows you to assess how your implicit, unexpressed values line up with your expressed values.

Priming happens on a micro level in a couple or family, too. When the relationship in a couple or between a parent and child becomes fraught with bad feelings, a person becomes primed to see the negative qualities or behavior they expect and -- like with the gorilla -- may completely miss unexpected, positive moments for which they are not primed.

In "How to Talk so Kids Will Listen and How to Listen so Kids Will Talk," Elaine Mazlish and Adele Faber talk about "catching" kids being good; noticing and calling out when a kid does the right thing. They present it as a way for kids to feel that they can succeed, which is important. But just as important is what "catching" a kid doing good does for a parent. It re-primes him or her.

If you find yourself counting basketball passes all the time with your spouse or kid -- watching for them to do the expected and annoying thing -- re-prime yourself. Look for good, look for gorillas. They're more common than you think.